Can privacy coexist with technology that reads and changes brain activity?

Advances are coming fast, encompassing a variety of approaches, including over-ear headphones that can distinguish between hunger and boredom; implanted electrodes that translate speaking intentions into actual words; and bracelets that use nerve impulses to type without a keyboard.

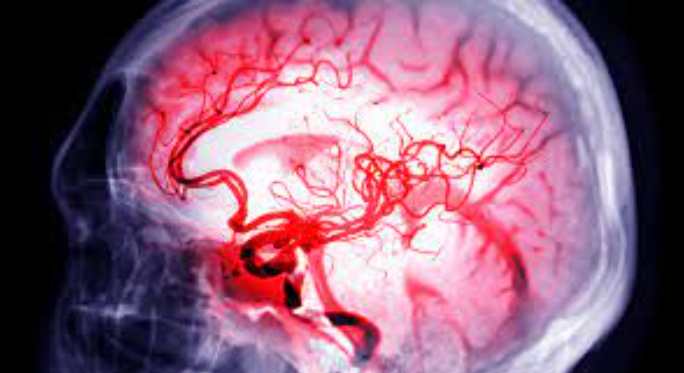

Today, paralyzed people are already testing brain-computer interfaces, a technology that connects brains to the digital world, with brain signals alone, users have been able to shop online, communicate and even use a prosthetic arm to drink from a cup. The ability to hear, understand, and perhaps even modify neural chatter could change and improve people’s lives in ways that go far beyond medical treatments, but these abilities also raise questions about who has access to our brains and with what what purposes.

The ability to pull information directly from the brain, without relying on speaking, writing or typing, has long been a goal for researchers and doctors trying to help people whose bodies can no longer move or speak. Implanted electrodes can already record signals from movement areas of the brain, allowing people to control robotic prosthetics.

Technology that can change brain activity already exists today, as medical treatments, these tools can detect and prevent a seizure in a person with epilepsy, for example, or stop a tremor before it occurs. Researchers are testing systems for obsessive-compulsive disorder, addiction, and depression. But the power to precisely change a working brain directly, and as a result, a person’s behavior, raises troubling questions.

As neurotechnology advances, scientists, ethicists, companies, and governments seek answers about how, or even whether, to regulate brain technology. For now, those answers are entirely up to who you ask, and they come against a backdrop of increasingly invasive technology that we’ve grown surprisingly comfortable with. We let our smartphones monitor where we go, what time we fall asleep, and even whether we’ve washed our hands for a full 20 seconds. Combine this with the digital breadcrumbs we actively share about the diets we try, the shows we eat, the tweets we love, and our lives are an open book.

Those details are more powerful than brain data, your email address, your notes app, and your search engine history reflect more of who you are as a person, your identity, than our neural data.

A lack of ethical clarity is unlikely to slow the pace of the coming neurotechnological rush, but careful consideration of ethics could help shape the trajectory of what’s to come and help protect what makes us most humans. What do you think?

Responses