Surprisingly, humans recognize screams of joy faster than screams of fear.

Screams of joy appear to be easier for our brains to understand than screams of fear, a new study suggests. The results add a surprising new layer to scientists’ long-held notion that our brains are wired to quickly recognize and respond to cries of fear as a survival mechanism.

The study looked at different types of yelling and how they are perceived by listeners. For example, the team asked participants to imagine being attacked by an armed stranger in a dark alleyway and screaming in fear, and imagine their favorite team winning the World Cup and screaming with joy. Each of the 12 participants produced seven different types of screams: six emotional screams (pain, anger, fear, pleasure, sadness, and joy) and one neutral scream where the volunteer simply yelled out loud the vowel ‘a’.

Then as homework for the research, 33 volunteers were asked to listen to the screams and were given three seconds to classify them into one of seven different screams. In another assignment, 35 different volunteers were presented with two screams, one at a time, and asked to classify the screams as quickly as possible while still trying to make an accurate decision as to what type of scream it was, whether alarming screams or alarming screams. of pain, anger or fear or non-alarming cries of pleasure, sadness or joy. Participants took longer to complete the task when it involved fear and other alarming cries, and those cries were less easily recognizable than non-alarming.

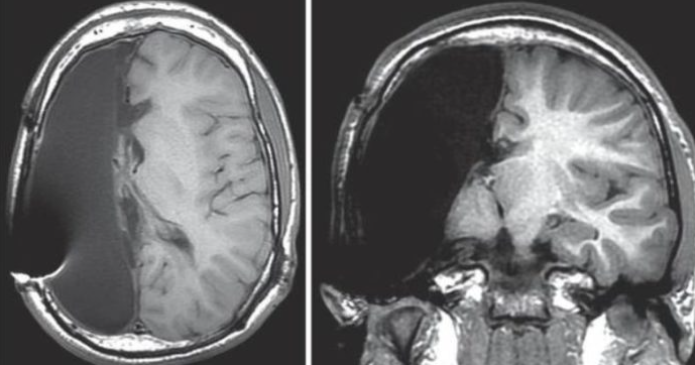

In another experiment, 30 different volunteers underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging while listening to screams. Less alarming yells elicited more activity in the auditory and frontal regions of the brain than more alarming yells, the team found, though why we respond that way remains unclear.

The study shows call communication and the ways we understand vocalization is diverse in humans, compared to other mammals whose calls are often associated with alarming situations such as danger. The work challenges the dominant view in neuroscience that the human brain is primarily tuned to detect negative threats.

Responses